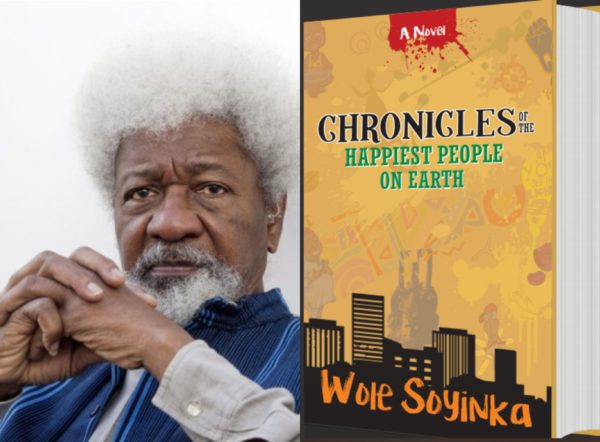

By Ben Okri

Wole Soyinka’s new novel tells the multidimensional story of a secret society dealing in human parts for sacrificial uses, whose members encompass the highest political and religious figures in the land. It details how the conspiracy and cover-up of this quasi-organisation affect not only the life of the nation but, more specifically, the lives of four friends.

This is essentially a whistleblower’s book. It is a novel that explodes criminal racketeering of a most sinister and deadly kind that is operating in an African nation uncomfortably like Nigeria. It is a vivid and wild romp through a political landscape riddled with corruption and opportunism and a spiritual landscape riddled with fraudulence and, even more disquietingly, state-sanctioned murder.

This is a novel written at the end of an artist’s tether. It has gone beyond satire. It is a vast danse macabre. It is the work of an artist who finally has found the time and the space to unleash a tale about all that is rotten in the state of Nigeria. No one else can write such a book and get away with it and still live and function in the very belly of the horrors revealed. But then no other writer has Soyinka’s unique positioning in the political and cultural life of his nation.

Chronicles from the Land of the Happiest People on Earth opens with the sentence: “Papa Davina… preferred to craft his own words of wisdom. Such, for instance, was his famous ‘perspective is all’.” This alerts us from the beginning that we need aesthetic distance to make sense of the twists and turns, the baroque engineering, the curious structure and the paradoxically exuberant tone of this strange novel.

Papa Davina is the religious guru, whose all-purpose spiritual ministry, Ekumenica, is an elaborate front for practices so sordid and monstrous that even when one learns what they are the mind still refuses to grasp them. He is in cahoots with the head of state, the wily and pragmatic Sir Goddie, and it seems that this racket, this secret society, encompasses the entire power structure of the land. Is this a metaphor for the extreme nature of corruption and lies that strangles the life out of that potentially great nation or is it a case where the metaphor is in fact the thing itself? If the latter, then the writer is dealing with one of the most existential problems in fiction, which is how a writer deals with the unspeakable in a medium in which things must be spoken of and a story told. How do you tell a story of the unspeakable?

Soyinka is one of Africa’s most representative writers. A poet, playwright, essayist, memoirist, activist and novelist, he was jailed in the 60s for his outspoken condemnation of the Nigerian civil war and was the first African recipient of the Nobel prize for literature in 1986. He has been one of the most caustic critics of dictatorships and bad governance in Nigeria. This novel is the fruit of all that experience. It is his first in 48 years and only his third. His debut, The Interpreters, was the story of a generation of friends, each one representing one of the gods or goddesses of the Yoruba pantheon. It opens with the sentence: “Metal on concrete jars my drinklobes.” His second, Season of Anomy, was his fictional and poetic response to the Nigerian civil war. In the intervening years he has written more than 20 plays, poems, autobiographies, polemics, and various forms of literary hand grenades. Apparently, it took the forced solitude of lockdown to compel him to finally write the novel he has carried in him for some time.

It is a portrait of how a generation betrays and is betrayed by the prevailing ethos of moral entropy.

At the heart of Chronicles… is the tale of a quartet of friends who form themselves into a fraternity called the Gong of Four and how they maintain their integrity and are drawn into the maelstrom of political life that surrounds them. In a microcosmic sense it is a portrait of how a generation betrays and is betrayed by the prevailing ethos of moral entropy.

One thing to be clear about from the outset is that with certain writers of highly individualised voices, highly cultivated ways of seeing, there is nothing you can do about their styles. It is an inescapable fruit of how they see the world. Like Henry James, like Conrad, like Nabokov, there is no choice but to get used to the style, to saturate yourself in it. But once you nestle into that tone, something wonderful happens and a rollercoaster ride of enormous vitality is the result.

It is a high-wire performance sustained for more than 400 pages and it makes for uncomfortable and despairing reading, but always elevated with a robust sense of humour and the true satirist’s unwillingness to take the pretensions of power seriously, even when it is murderous in effect.

There are many things to remark upon in this Vesuvius of a novel, not least its brutal excoriation of a nation in moral free fall. The wonder is how Soyinka managed to formulate a tale that can carry the weight of all that chaos. With asides that are polemics, facilitated with a style that is over-ripe, its flaws are plentiful, its storytelling wayward, but the incandescence of its achievement makes these quibbles inconsequential.

If you want to know what kind of novel can be written by someone who has survived as a sort of insider in a difficult land but who has kept their creative conscience and their powers of invention alive then Chronicles… answers that question. It is Soyinka’s greatest novel, his revenge against the insanities of the nation’s ruling class and one of the most shocking chronicles of an African nation in the 21st century. It ought to be widely read.