By Chidi Odinkalu

Three important documents released in the past week – respectively from Nigeria’s federal government and two by respected international NGOs, Chatham House and OXFAM – separately offer important insights into why the present effort to fight corruption in the country is stuck in a mire. Together, they offer a more coherent synthesis of how fighting corruption in Nigeria can achieve take off.

The first document is the 45-page National Anti-Corruption Strategy (NACS), mid-wifed by the attorney-general of the federation and minister of justice, Abubakar Malami, a Senior Advocate of Nigeria (SAN). The absence of a coherent strategy has been a major drag on the fight against corruption. The process of developing one was blighted by visceral inter-agency turf wars, which deferred its completion by over one year. From the wreckage of this conflict, the attorney-general’s department emerged victorious. The result was that other ministries, departments and agencies with complementary expertise on the subject were either relegated or excluded from the process. This absence of joined up thinking is evident in the resulting document. It is confused, self-contradictory and arguably worse than no strategy at all. It is an anti-climax.

The problems with this NACS are too many. Three illustrations will suffice. First, it lacks any clear diagnosis of why fighting corruption in Nigeria has proved so intractable. This is not for want of a recognition, on the part of the drafters, of the importance of such an undertaking. Attorney-General Malami begins his introduction to the strategy with the acknowledgement that “the fight against corruption in Nigeria has had a long history.” He thereafter meanders into some grandiose lingo, at the end of which he forgets to say what this history is and why it has deepened Nigeria’s corruption pathology rather than alleviate it. The result is that the NACS document does not, in any way, offer any assurance that this current phase of fighting corruption in Nigeria will suffer a fate different from its predecessors.

Second, the NACS offers no coherent narrative of the corruption challenge in Nigeria nor does it recognise any other actor in shaping or fighting it beyond the narrow halls of government. This is surprising because the drafters of the strategy begin by acknowledging the need for “a shared national understanding of what corruption is and what it is not”. They appear thereafter to suffer a collective lapse in memory or concentration because the document offers none. The strategy similarly promises “a new approach, which essentially builds on lessons from past efforts at fighting corruption in the country” but ends up merely seeking to “identify and close existing gaps in the anti-corruption initiatives currently in place”. This anaemic mission does not exactly need a strategy. It can easily be accomplished by an inter-agency working group.

Third, the underlying crisis of the NACS is an absence of a coherent thesis of Nigeria’s corruption crisis in its relationship to governance and state evolution. Lacking any such understanding, it fails to evince any need for popular ownership of the fight against corruption nor see any relationship between the nature and incoherence of the Nigerian state and Nigeria’s chronic corruption pandemic.

For a proper acknowledgement of this underlying challenge, one must look to the 53-page report, “Collective Action on Corruption in Nigeria: A Social Norms Approach to Connecting Society and Institutions”, recently launched by the Royal Institute of International Affairs, better known as Chatham House. This report focuses on developing “a new approach to anti-corruption” by investigating the “drivers of collective participation in corrupt practices” in Nigeria.

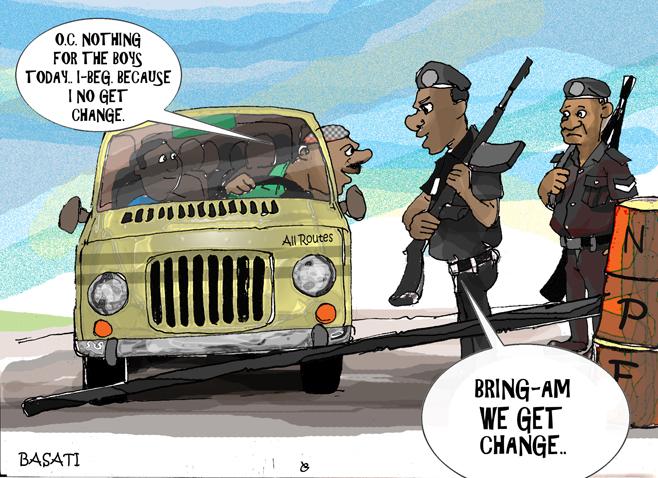

In what could easily be a summary of the shortcomings of the NACS, the Chatham House report laments that Nigeria’s focus has mainly been on “‘traditional’ legal and governance-based measures, emphasising the reform of public procurement rules and public financial management, anti-corruption laws and the establishment of various agencies tasked with preventing corruption and punishing those who engage in it.” While acknowledging the importance of these measures, the report emphasises the need “to foster a comprehensive shift in deeply ingrained attitudes to corruption at all levels of society.”

Its central argument, therefore, is that “Nigeria’s ongoing anti-corruption efforts must now be reinforced by a systematic understanding of why people engage in or refrain from corrupt activity, and full consideration of the societal factors that may contribute to normalising corrupt behaviour and desensitising citizens to its impacts.” It seeks to demonstrate how “this holistic approach would better position public institutions to engage Nigerian society in anti-corruption efforts.”

Among its major recommendations, the Chatham House report suggests that “anti-corruption efforts may have the greatest chance of success if they stem from a shared sense of responsibility and urgency – and thus foster collective grassroots pressure.” The consequences of this point for both analysis and strategy are radical. It means that the beginning of any anti-corruption strategy lies in political economy and inclusive civics. Unsurprisingly, Chatham House advocates an analysis and framing that gives “ownership and agency to Nigeria’s citizens.” The absence of a shared sense of common citizenship or the presence of fragmented national identity breeds competitive asset stripping of what should be a collective patrimony. It is the failure to realise or reflect this that makes the NACS so awfully deficient.

How this occurs is the focus of the contemporaneous, 56-page OXFAM report: “Inequality in Nigeria: Exploring the Drivers.” This report demonstrates a clear correlation, verging indeed on causation, between deepening inequality and growing corruption in Nigeria. As a point of departure, it asserts that Nigeria’s growing inequality and poverty problems are the result of “the ill-use, misallocation and misappropriation” of resources underpinned by what it calls “a culture of corruption and rent-seeking combined with a political elite out of touch with the daily struggles of average Nigerians.” One of the major drivers of this growing inequality is the prohibitive cost of governance “because it means that few resources are left to provide basic essential services for the wider, growing Nigerian population.”

Far from serving as a tool of equity, Nigeria’s tax policy, to the extent that one exists, is “largely regressive: the burden of taxation mostly falls on poorer companies and individuals.” This feeds a system of dependency on one natural resource, hydro-carbons. The underlying edifice of elite plunder that the report identifies is a deliberately manufactured policy innumeracy, such that the country cannot and does not know how much oil it extracts or lifts. To camouflage this egregious failure, we use the template of “grand crude oil theft” for which, by the way, no one has ever been held to account. This manufactured state incapacity drives institutional failure which is merely the symptom that the NACS focuses on.

This, precisely is the reason why the NACS document disappoints terribly: it focuses on a few symptoms without attempting to show an understanding of the underlying ailments that condemn successive anti-corruption efforts in Nigeria to certain failure. Had it attempted to do so, the strategy would have anchored its approach on enlightened political leadership that seeks to build a more inclusive and more equitable society for all in the country. It would have addressed the need for an economic programme that offers hard working Nigerians a path to legitimate livelihood and a stake in paving such a path. It would also have addressed the need to develop a common vocabulary to embed popular ownership of this anti-corruption effort. With no effort to contemplate, let alone include these in the document, the NACS could well end up like its predecessors: much heralded but tragically stillborn. It was not supposed to be such a missed opportunity.

Chidi Odinkalu is Senior Visiting Fellow at the Centre for the Study of Human Rights at the London School of Economics & Political Science (LSE) & a member of the Board of Directors of The Integrity Organisation. Twitter: @ChidiOdinkalu