By Colbert Gwain

“Whistleblower protection can only succeed when civil society remains actively engaged and holds authorities accountable for their actions.” – Anna Myers, Executive Director, Whistleblowing International Network (WIN).

Muteff may be a little-known local village kaleidoscope situated off the jaws of Laikom (seat of the traditional administration of the Kom Kingdom in the Boyo Division of the North West Region of Cameroon), but what happens there sometimes has unimaginable global dimensions. In that village, there once lived a certain Bobe Nganguo (considered the wealthiest individual by village standards). Originally, he used to be a likable and outgoing individual; but since he hated wrongdoing and corrupt practices carried out by his fellow community leaders, he opted for a secluded lifestyle (rather than confront any individual involved in malpractice).

Contrary to Bobe Nganguo’s decidedly far-removed attitude, his closest neighbor, a certain Yindo Tanghe was not only dangerously outspoken but also thick-skinned. He was so sensitive to corrupt practices and malfeasance in the community, to such an extent that even in the traditional ‘Chong’ fraternity or in the village traditional council, he would expose any malpractice and tell anybody who cared to listen that he would prefer to die than sit back and watch wrongdoing triumph in the community.

He would openly declare his readiness to confront any accused leader, even in Laikom where the highest Kom traditional court is lodged. In the process, he was hated by virtually everybody in the village who had a leadership position and had a skeleton in his cupboard. Although he was nowhere close in wealth to Bobe Nganguo (as he relied mostly on kola nut vending for a living), he was the first to sound off how self-sufficient he was to rely on the commonwealth of the community for survival.

Unlike Bobe Nganguo, who stayed aloof despite noticing malpractices in the Muteff community, Yindo Tanghe might have been the forerunner of the community whistleblower that the world so badly needs today. Like Yindo Tanghe, you might never have heard of Li Wenliang, the Chinese medical doctor who blew the lid off authorities’ secrecy in trying to stem the spread of the coronavirus in Wuhan province. Dr. Li was at a hospital where infected patients were being treated. Witnessing the intensity of the virus and its ability to spread uncontrollably across China and beyond, he issued an alert on an online platform, WeChat.

Rather than further investigations to ascertain the claim and take appropriate steps to stem it, Chinese authorities instructed the police to call Li Wenliang to order. He was immediately summoned and accused of “spreading rumors.” Although he later contracted the disease and died, Chinese authorities officially apologized to him for not taking his early warning alert seriously. What followed was quarantining and the complete lockdown of Wuhan and other affected regions of China. By then, the disease had spread beyond China. The World Health Organization (WHO) declared it a public health concern and later, a pandemic. Within a twinkle of an eye, it had spread across the world.

The point to be made is that the COVID-19 pandemic could have been avoided if Chinese authorities had listened to Dr. Li.

Cameroonians are witnessing the same scenario being played out at the Football Federation with the 4th Vice President, Njalla Quan Jr., being suspended for daring to not only challenge the managerial style of President Eto’o Fils but also denounce misconduct at the FA. As FECAFOOT’s Vice President in charge of Marketing, Njalla Quan recently went public, decrying the opacity with which contracts were signed at the FA, broad-daylight match-fixing, and above all, Eto’o Fils’ unwillingness to begin respecting campaign promises. In his public outcry, Njalla Quan explained how he had tried repeatedly to draw Eto’o Fils’ attention to the issues raised and how he had been mocked several times.

Barely a few days after he blew the whistle, President Eto’o Fils signed a communiqué suspending him from the Executive Bureau of the Cameroon FA. This signaled a very dangerous precedent for whistleblowers in Cameroon as brilliantly captured in last week’s edition of Profiles International.

To better understand the relevance of this reflection and why Cameroon urgently needs a whistleblower protection law (so that what happened to Henry Njalla Quan Jr. doesn’t become the new normal), we must understand what it means to be a whistleblower. Broadly speaking, a whistleblower is an individual who, without authorization reveals private or classified information about an organization, usually relating to wrongdoing or misconduct (like in the case of Njalla Quan).

Worthy of note is the fact that such information must be of public interest and the evidence the whistleblower is revealing must be capable of withstanding public scrutiny. And this is likely the case with Njalla Quan’s claims as after his outing, many more Club Presidents are speaking out. Although the term was first used to refer to public servants who made known government’s mismanagement, waste, or corruption, it now covers the activity of every individual who is concerned about public probity and alerts a wider group to setbacks to their interests as a result of waste, corruption, fraud, or profit-seeking. The suspended Vice President of FECAFOOT did exactly that. The swiftness with which he was suspended (coupled with the subsequent threats to his life), speaks to the need for a whistleblower protection law in Cameroon if cases of corruption, embezzlement, and malfeasance are to be checked.

Yindo Tanghe might have been successful in denouncing wrongdoing in high places in Muteff village because of the immunity he had by his closeness to the Kom palace authorities, but Henry Njalla Quan Jr. is fighting extremely powerful forces and only protective whistleblower legislation can save people like him. He may not be the first Vice President to have identified wrongdoing within the FA, but his predecessors had behaved like the above-cited Bobe Nganguo of Muteff by deciding to “let sleeping dogs lie.”

Since their actions usually always benefit society rather than the individual whistleblower, they (who usually risk their lives to protect the public interest as Njalla Quan just did), must be encouraged and protected. The United States is a shining example in this domain. Their “False Claims Act” allows even private citizens to file lawsuits on behalf of the Federal Government against companies and individuals suspected of defrauding the government or any other institution. If the court rules against the company, institution, or individual, the whistleblower is entitled to half of the damages won by the government in the lawsuit.

The government of Cameroon may not have any policy or legislation encouraging and protecting whistleblowers but we know for a fact that a certain brave Tifang Peter, C.E.O of a Bamenda-based Organization for the Protection of Consumers Sovereignty, OCOSO, took a contractor to the Bamenda High Court for the poor implementation of a government contract over the Ngen Junction bridge and the contractor escaped from the country before the court could go substantial on the matter.

Jurisprudential evidence exists of the benefits the Cameroonian society has recorded thanks to the risky whistleblowing efforts of individuals like Njalla Quan Jr. A case that vividly comes to mind is that of Mounchipou Seidou, Minister of Posts and Telecommunications in Biya’s government in the 90s. When the leading opposition SDF MPs presented irrevocable evidence of his corruption and embezzlement scandals in that ministry, Yaounde authorities had no choice but to allow him to go to court. He was imprisoned.

Earlier rights activists like Albert Mukong, Godji Dinka, Vewese, Wilfred Tasang, Mancho Bibxiy, and Agbor Balla, can never be under-looked as whistleblowers in their own right.

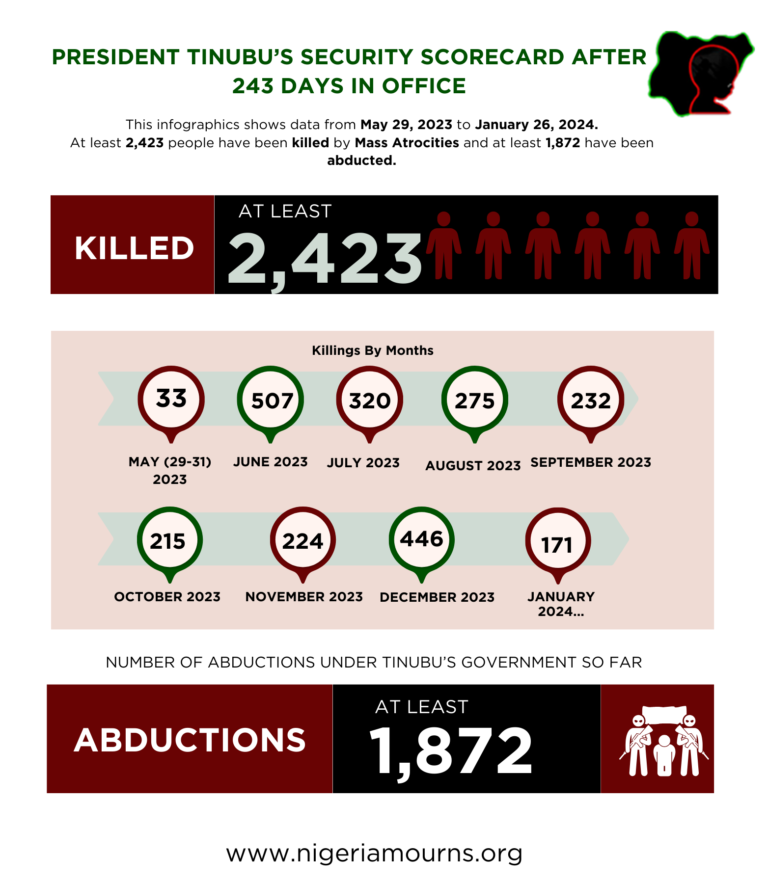

With such compelling evidence to the effect that governments around the world only make greater strides in the fight against corruption, embezzlement, and misconduct when individuals within and without the institutions are protected and encouraged to speak out against malfeasance, the government, civil society, and the media must jointly work to build public support and confidence in whistleblowers as well as initiate advocacy for effective protection and reward for them. Without a legal instrument backing whistleblowers in Cameroon and elsewhere in Africa, their job would be complicated.

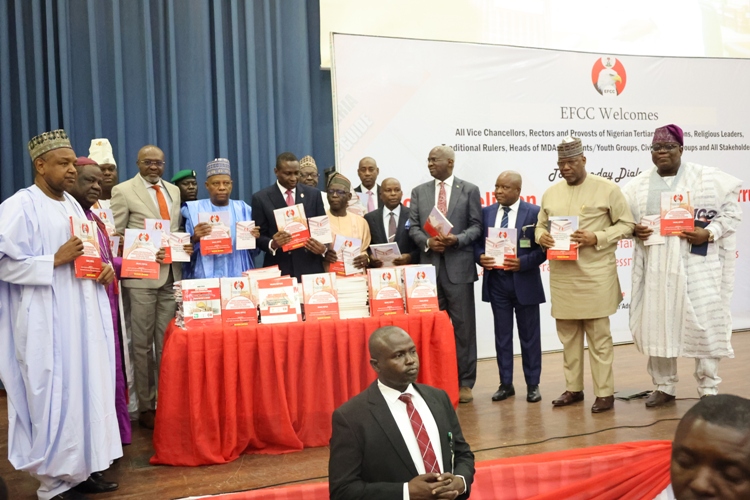

Godwin Onyeacholem, leading Nigerian whistleblowing advocate and Project Coordinator of Corruption Anonymous (CORA), an initiative of the African Centre for Media & Information Literacy (AFRICMIL), in a recent article published by the International Centre for Investigative Reporting (ICIR), notes that “the duty to blow the whistle can only be enhanced when citizens know that once they blow the whistle, there would not be retaliation, or if there is retaliation, they would be protected.” He is right. If Yindo Tanghe in the above-cited Muteff case didn’t know he would have protection from the revered Kom fondom, he wouldn’t have blown the whistle such as he did.

If many more Henry Njalla Quan Jrs. have to be encouraged to blow the whistle in their various workplaces where they find wrongdoing, including in the military-industrial complex, we would need to all join in advocating a whistleblower protection law for Cameroon. The United Nations must also quickly get back to work to reinforce and redraft protection mechanisms for whistleblowers, including a standalone convention and optional protocols. It must do a better job by incentivizing whistleblowers across the world and conditioning development aid to member States after the COVID-19 havoc, on the domestication of legislation promoting whistleblowing both in the public and private sectors as well as in the military.

Colbert Gwain is a digital space immigrant, an accomplished author, radio host, and content creator known for his work at The Colbert Factor. Additionally, he actively contributes as a Commitment Maker for the UN Women Generation Equality Action Coalitions. Colbert identifies himself as an African Citizen merely residing in Cameroon, driven by his unwavering support for the Africans Rising campaign, which advocates for a #borderless Africa.

The Colbert Factor is a non-profit news organization committed to providing unbiased and informative coverage. We greatly depend on your financial support to sustain our operations. If you appreciate insightful and analytical articles like the one you are currently reading, please consider contributing today @ 677852476. By doing so, you would be helping to uphold the principles of a free press.