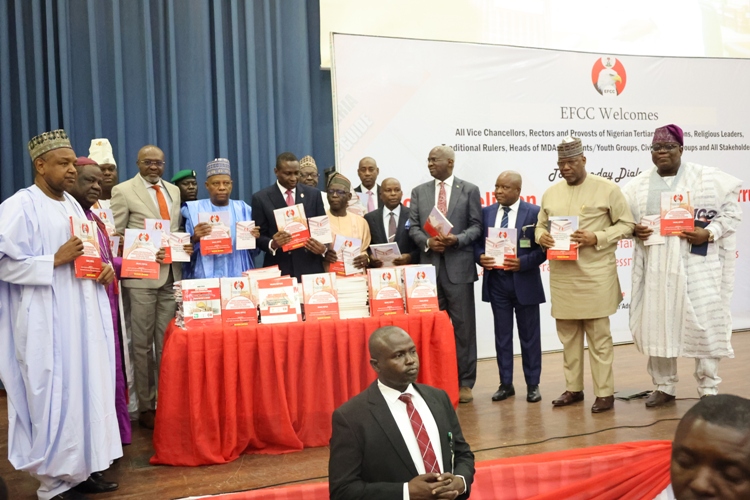

Winding up its last meeting in 2016, the Federal Executive Council approved the adoption of whistle-blowing as a veritable tool in the fight against corruption in the country. This is long overdue, given that it has become an effective weapon globally, especially in countries where the anti-graft campaign is a success story.

Nigerians, who join the anti-corruption caravan as whistle-blowers, will be rewarded handsomely, according to the Federal Government. They will take home between 2.5 per cent and five per cent of funds or property that might be recovered based on the information they provide. The latest strategy will serve as a stop-gap measure until the National Assembly passes a bill for the protection of whistle-blowers, pending before it.

An online portal has been set up at the Ministry of Finance, where whistle-blowers could submit their information, supported by evidence on looting, mismanagement, misappropriation of public funds, assets or bribe-taking and the amount involved. Specificity is the watchword.

What whistle-blowing can do as a public interest vehicle is demonstrated in recent media reports that it was an artisan who exposed the brand new 47 Sport Utility Vehicles and buses that were parked at the Abuja home of a retired Federal Permanent Secretary, where he had gone to do some repairs. With such mass of vehicles, hardly seen in most auto malls, he smelt a rat and reported the matter to the Economic and Financial Crimes Commission. The vehicles were allegedly bought for N1.5 billion, part of the N27 billion insurance premium of deceased workers of the Power Holding Company of Nigeria, to which officials have denied relatives access.

Public office holders in Nigeria are notorious for looting the treasury. This fact is well documented by the World Bank, International Monetary Fund, African Union and other anti-graft watchdogs such as the Global Financial Integrity, a US-based group. The GFI, in a report it prepared based on World Bank and IMF data, asserted that $182 billion was illicitly taken away from Nigeria and laundered offshore between 2000 and 2009.

A report by AU’s special committee, which a former President of South Africa, Thabo Mbeki, headed, also confirmed in 2014 such financial heist. Out of every $60 billion illegally transferred out of Africa, the AU said, $40 billion was traced to Nigeria, in a haemorrhage that has been on for over four decades. President Muhammadu Buhari, who took the loot recovery campaign to the global stage during the 70th General Assembly of the United Nations last October, said in the 10 years to 2015, about $150 billion was looted. This explains why Nigeria is ranked 136th out of 168 countries, in the Corruption Perception Index of 2015.

This stealing binge is epitomised in the sharing of $2.1 billion by the Office of the National Security Adviser under the Goodluck Jonathan administration, and the $153 million cash allegedly siphoned from the vault of the Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation by a former minister and handed over to some bank managing directors for safe-keeping. When such huge raw cash is brazenly stolen from an otherwise safe vault, as it also affected the Central Bank of Nigeria during this better-forgotten era, much against the extant Anti-Money Laundering Act, the magnitude of the theft could be inscrutable.

Contract scamming, bribery cases like the Halliburton scandal and the ongoing Malabu oil corruption trial that involves $446 million in Italy; tax evasion; and trade under-invoicing are other fertile avenues for such dirty deals. But these offences do not occur without a chain of collaborators. As a result, banks, allied financial institutions and estate firms should be the primary focus of whistle-blowers in the search for evidence for them to crackle.

For the whistle-blowing policy to be effective, the Attorney-General of the Federation should enrich the bill, which has passed the Second Reading in the Senate, with details of government’s position. As presently framed by the FEC without legal guarantees, the policy is a non-starter. An Act of parliament should be a firm warranty for the whistle-blower to get the reward and secure protection from harassment, intimidation and job loss. The non-existence of such legal underpinnings was why an employee of the National Women Development Centre, Abuja was fired a few years ago, for exposing the embezzlement of N300 million meant for poverty alleviation.

The adoption of global best practices, therefore, will drive Nigerians to own the anti-graft campaign, contrary to the reality of the moment: it runs only as a government campaign or, worse still, a one-man riotous effort – Buhari’s.

In the US, after the False Claims Act of 1863, which allowed private parties to bring suits against corporations and persons that tried to defraud the government, and were entitled to half of the recovery made, states took it over by passing their own versions of the law to guide the implementation of the policy. Since 1986, when the Act was strengthened to give more rights to the whistle-blower, 3,000 court cases have been filed by individuals with $3 billion paid as reward. The government has intervened in only 21 of such cases.

Similarly, the United Kingdom strengthened its whistle-blower protection law with the Public Interest Disclosure Act in 1998. Under it, any employee subjected to retaliation can be heavily compensated. The highest award to date is £5 million.

Consequently, the whistle-blowing policy offers Nigeria a new vista in the anti-graft drive. Government’s commitment is critical. There should be no room for the carapace indifference it has been displaying since Abdulmumin Jibrin spilled the beans last year on budget-padding in the House of Representatives.

This piece first appeared on January 15, 2017, in http://punchng.com